Reclaiming Our Place in the Living World

Part 5: Pathways to Nature Connectedness for Wellbeing

This article continues from my recent four-part series exploring the findings of my Psychology thesis, Combatting the climate crisis: Cueing threat perception and biophilia to trigger intended pro-environmental behaviour (Saleeba, 2021). In that series, I examined the psychological and emotional dimensions of human–nature relationships, the role of biophilia in wellbeing, and the implications for behaviour change in the context of environmental crisis. Here, the focus shifts from theory to practice offering evidence-based pathways for individuals who want to reclaim nature connectedness as an intrinsic part of their human condition, and to harness it for their own wellbeing.

Read: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4.

Humans evolved in continuous relationship with the natural world. For most of our history, our survival, culture, and sense of self were interwoven with the living systems around us. Today, many people live in environments where nature is distant, obscured, or incidental to daily life. The result is a form of disconnection that can diminish both individual wellbeing and collective care for the environment.

Research shows that nature connectedness is not simply about spending time outdoors. It is a psychological state a felt sense of relationship with the rest of nature that supports mental health, life satisfaction, and pro-environmental behaviour (Capaldi et al., 2014; Pritchard et al., 2020). This article explores practical pathways for reclaiming this intrinsic part of our human condition.

Why Nature Connectedness Matters for Wellbeing

A strong relationship with nature is associated with lower levels of stress, improved mood, increased vitality, and greater life satisfaction (Capaldi et al., 2014; Pritchard et al., 2020). It also predicts pro-social behaviours such as cooperation, empathy, and stewardship. Importantly, nature connectedness differs from nature exposure: being in a green space does not necessarily lead to a sense of belonging within the living world (Mayer & Frantz, 2004).

Studies have identified key dimensions of nature connectedness, including emotional affinity, cognitive identification, and experiential familiarity. My research highlighted the role of emotional cues in strengthening biophilic responses helping people feel part of, rather than separate from, natural systems.

Barriers to Connection

Several factors make sustained nature connectedness less common in modern life:

Urbanisation and built environments that limit everyday access to biodiverse spaces.

Digital saturation, with leisure and work time dominated by screen-based activities.

Psychological distance, where nature is perceived as something “out there” rather than integrated into identity.

Cultural narratives that position humans as separate from, or superior to, other species.

Understanding these barriers helps us identify where and how reconnection can occur.

Pathways to Nature Connectedness

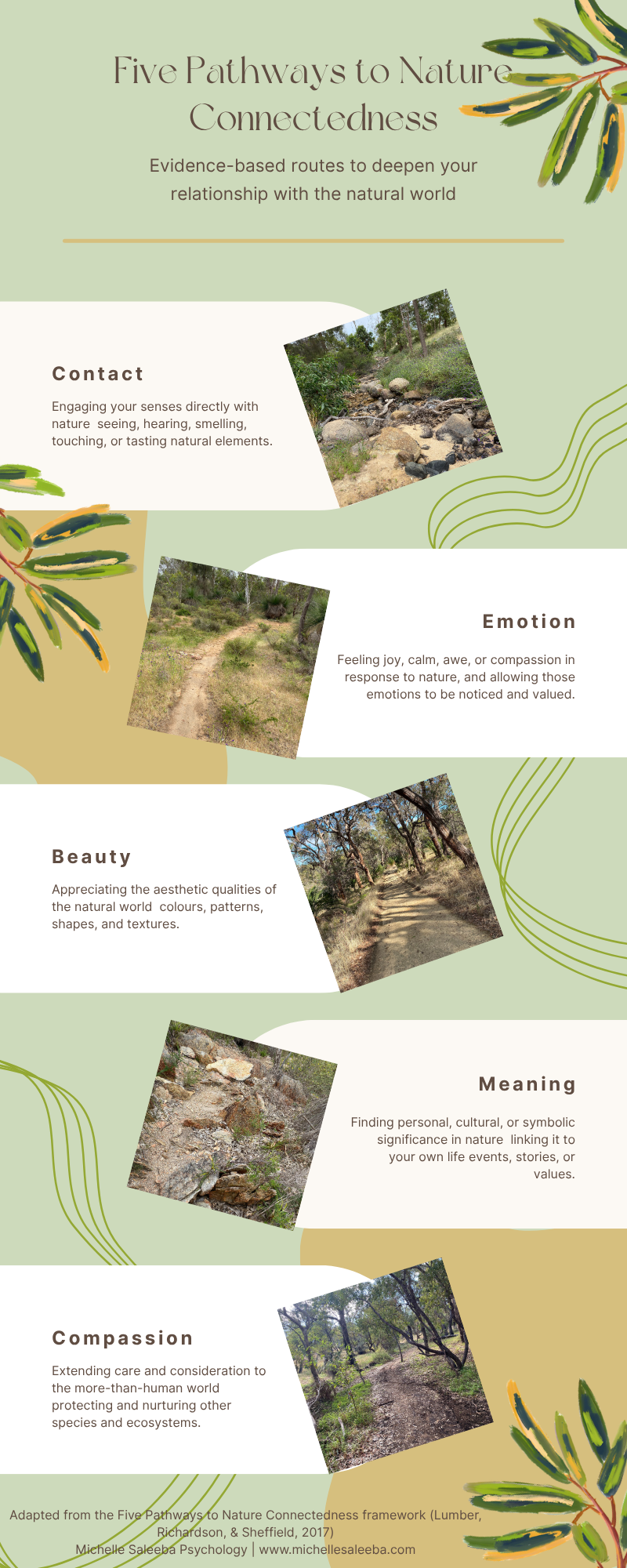

The Five Pathways to Nature Connectedness (Lumber et al., 2017) provide a useful evidence-based framework for deepening our relationship with the natural world. These pathways can be adapted to personal circumstances and therapeutic contexts.

Contact – Direct sensory engagement with nature.

Simple actions such as walking barefoot on grass, noticing the scent of rain, or tending to plants can increase sensory awareness and anchor attention in the present moment. In therapy, this aligns with mindfulness and sensory grounding practices.Emotion – Experiencing feelings of joy, awe, compassion, or calm in response to nature.

Emotional experiences watching the light shift through leaves, hearing birdsong at dawn help to create memorable and meaningful nature encounters. My thesis findings emphasised that emotional resonance is a key driver of enduring connection.Meaning – Finding personal, symbolic, or cultural significance in nature.

This might include marking life events with nature-based rituals, creating art inspired by landscapes, or reflecting on cycles and seasons as metaphors for change.Compassion – Extending care and ethical consideration to non-human life.

This could involve wildlife-friendly gardening, reducing waste that harms ecosystems, or participating in conservation projects. Compassion strengthens identity as a participant in, rather than a consumer of, natural systems.Beauty – Appreciating aesthetic qualities in the natural world.

Observing colour, form, and pattern in leaves, clouds, or shells encourages mindful attention and fosters appreciation. Photography, sketching, or simply pausing to notice beauty can heighten this pathway.

Integrating Nature Connection into Daily Life

Reconnection does not require wilderness access or large amounts of time. Consistency and intentionality matter more than scale.

Examples include:

Starting or ending the day with a short period outdoors.

Keeping a simple nature journal to record observations, drawings, or reflections.

Observing seasonal changes in a familiar location.

Taking micro-breaks to look at the sky, notice air movement, or listen to local bird calls.

Combining nature connection with existing routines such as walking, commuting, or creative hobbies.

For Clinicians and Wellbeing Practitioners

Nature connectedness can be incorporated into psychological support in ways that are flexible and accessible:

Assessment: Explore a client’s current relationship with nature, including past positive experiences and current barriers.

Metaphor: Use nature-based metaphors to support meaning-making in therapy.

In-session activities: When possible, integrate outdoor elements such as short walks or observing natural objects into sessions.

Ethics and access: Consider safety, accessibility, and cultural relevance. Recognise that some clients may have negative or traumatic associations with certain natural settings.

Conclusion

Nature connectedness is a personal and collective resource. Reclaiming it supports mental health, fosters a sense of belonging, and encourages actions that sustain the living world (Capaldi et al., 2014; Pritchard et al., 2020). The pathways described here offer starting points for embedding nature into daily life and professional practice.

Even small, intentional steps pausing to notice beauty, engaging the senses, expressing care can help restore this fundamental relationship. In doing so, we take back an intrinsic part of being human, with benefits that extend far beyond the individual.

Closing the Series

This article concludes the current series translating my thesis findings into accessible, practice-focused resources. The earlier four articles explored the psychological foundations of nature connectedness, the role of emotional and cognitive cues in biophilia, and the wider wellbeing and environmental implications of restoring our relationship with the natural world. Together, they offer both the “why” and the “how” of nature connection. Readers who would like to explore the theoretical background in more depth can return to the earlier instalments, while those ready to begin can start experimenting with the pathways outlined here.

References

Capaldi, C. A., Dopko, R. L., & Zelenski, J. M. (2014). The relationship between nature connectedness and happiness: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 976. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00976

Lumber, R., Richardson, M., & Sheffield, D. (2017). Beyond knowing nature: Contact, emotion, compassion, meaning, and beauty are pathways to nature connection. PLoS ONE, 12(5), e0177186. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177186

Mayer, F. S., & Frantz, C. M. (2004). The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24(4), 503–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2004.10.001

Pritchard, A., Richardson, M., Sheffield, D., & McEwan, K. (2020). The relationship between nature connectedness and eudaimonic well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(3), 1145–1167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00118-6

Saleeba, M. (2021). Combatting the climate crisis: Cueing threat perception and biophilia to trigger intended pro-environmental behaviour (Thesis, Murdoch University).