Enhancing resilience and adaptive capacity through creativity

April 28, 2022

Art and creative pursuits have been shown to play a unique role in lowering stress, while enhancing individual, social and community resilience (Kaimal et al., 2016; Shand, 2014). Engaging in creative practices can aid with the reinforcement of a person's resilience trajectory, establishing healthy long-term relief and management solutions as individuals and communities overcome the disequilibrium of adverse experiences (Bonanno, 2021; 2004; Bonanno et al., 2012; Shand, 2014). There is a complex interaction of determinants directing how individuals and systems respond to distinct types of stressful experiences (Bonanno, 2021; 2004; Southwick et al., 2014). Learning, or re-learning, how an individual or group senses, perceives and responds, and building adaptive response capacity, is essential to constructive problem solving and functionality, including supporting healthy workplace communication and team cohesion. This ability to reframe stressful experiences and to find meaning in adversity is a crucial element of resilience (Bonanno, 2021; McGonigal, 2015) and primary outcome from therapeutic arts engagement (Putland, 2012).

Resilience is most often reported as a multifaceted, multileveled construct and understood colloquially as adapting to, or bouncing back from adversity (Bonanno et al., 2012; Southwick et al., 2014), but one of the challenges of defining the construct is it holds different meanings for different people (Shand, 2014). Resilience can carry specific meaning within organisational contexts, whilst at the same time transcending occupational boundaries and developmental stages (Sinclair & Britt, 2013). Frequently explored through a theoretical lens of deficit or recovery and seen as a disposition that requires ‘building,’ more recent clinical understanding positions resilience as encompassing states beyond a person’s capacity to ‘bounce back’ after adversity and views individuals as inherently resilient (Bonanno et al., 2012; Bonanno, 2021; Southwick et al., 2014). Shand (2014) in a discussion of strength focused and socio-ecological approaches to resilience development through the arts, defines resilience as an active process demonstrated as an exhibition of strength during challenging times. Engagement in arts activities provides an opportunity to experience the tension and difficulty that accompanies being a learner and provides the opportunity to explore internal strengths in turn enhancing problem solving abilities and the development of a transferable aptitude for exploring connections between unrelated phenomena.

Opportunities to enhance creativity and imagination are crucial to fostering resilience because they develop the competence and skill to innovate, problem solve, communicate, collaborate, and critically reflect. All of which are described as essential workplace skills in the Future of Jobs Report 2020 (World Economic Forum). Workplace learning that focusses on enhancing creative thinking and skill building not only augments individual mental wellbeing by building emotional regulation, impulse control, self-awareness, and reduced reactivity to stressors (Kaimal et al., 2016; Putland, 2012; Shand, 2014) but simultaneously offers employees non-linear professional growth that promotes future focused skill development.

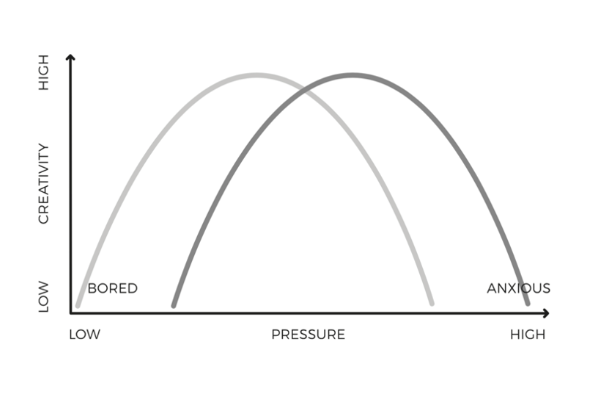

The human brain, however, has evolved to create cognitive shortcuts and then follow these straightforward pathways as a default. This results in our perception, ideas and creativity not getting much of a workout unless we purposefully stimulate ourselves with new experiences, ideas, and ways of thinking and doing. Challenging these short cuts, assumptions, and biases with a process where obvious and clear ways of understanding are no longer available to us allows creativity to thrive, more so when there is some pressure and limitation thrown into the mix (McGonigal, 2015).

Non-linear professional development and workplace learning such as the Art of Communication and Perception, move participants out of their habitual way of observing, perceiving, and interacting, challenging them to communicate with a vocabulary different to the one they use in their usual job role.

Figure 1. The creative process as an inverted-U.

The intention in stimulating low levels of stress with an activity that is ambiguous and a little uncomfortable, pushes the participants into the sweet spot of creative thinking promoting cognitive flexibility (Gabrys et al., 2018). Cognitive flexibility is vital for creative thinking and problem solving. It protects against cognitive biases and has been associated with greater resilience (Vartanian, 2016), important attributes for optimal functioning within complex work environments.

The two Creative Wellbeing workshops I share, Art Skills – 2D Foundations and the Art of Communication and Perception, offer distinct methods for organisations to bring creativity, connection and fun to the heart of employee learning and development and mental and emotional wellbeing.

References

Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely adverse events? American Psychologist, 59, 2028.

Bonanno, G. A., Westphal, M., & Mancini, A. (2012). Loss, Trauma, and Resilience in Adulthood. Annual Review of Gerontology & Geriatrics, 32, 189.

Bonanno, G.A. (2021). The end of trauma: How the new science of resilience is changing how we think about PTSD. Hachette, NY.

Gabrys, R. L., Tabri, N., Anisman, H., & Matheson, K. (2018). Cognitive control and flexibility in the context of stress and depressive symptoms: The cognitive control and flexibility questionnaire. Frontiers in Psychology, 2219.

Kaimal, G., Ray, K. & Muniz, J (2016). Reduction of cortisol levels and participants' responses following art making, Art Therapy, 33, 2, 74-80.

McGonigal, K., (2015). The Upside of Stress: Why stress is good for you and how to get good at it. Penguin Random House, NY.

Putland, C. (2012). Art and Health — A Guide to the Evidence. Arts and Health Foundation.

Shand, M. (2014). Understanding and building resilience with art: A socio-ecological approach. [Thesis]. Joondalup: ECU.

Sinclair, R. R., & Britt, T. W. (2013). Building psychological resilience in military personnel: Theory and practice (pp. xi-268). American Psychological Association.

Southwick, S. M., Bonanno, G. A., Masten, A. S., Panter-Brick, C., & Yehuda, R. (2014). Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. European journal of psychotraumatology, 5(1), 25338.

Southwick, S., Douglas-Palumberi, H., & Pietrzak, R. (2014). Resilience. In M. J. Friedman, P. A. Resick, & T. M. Keane (Eds.), Handbook of PTSD: Science and practice (2nd ed., pp. 590-606). New York: Guilford Press.

Vartanian, O. (2016). Attention, Cognitive Flexibility, and Creativity: Insights from the Brain. In J. Kaufman & J. Baer (Eds.), Creativity and Reason in Cognitive Development (Current Perspectives in Social and Behavioral Sciences, pp. 246-258). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

World Economic Forum. (2020, October). The future of jobs report 2020. Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum.

Michelle Saleeba Psychology

Subiaco | Outdoors | Online